Anatomy for Artists -

Realistic Spine Animations

Anatomy for artists usually covers bones and muscles structures, as well as the movement of the joints.

The movement of the spine, for some reason, remains surprisingly un-charted in most books and websites.

For animators this is a serious “black hole” in understanding how our body moves.

If you wish to create realistic spine animations, and move your characters in a convincing way, you need to learn how the different parts of the spine move.

Here is what you need to know:

Not all parts of the vertebral column can move the way we tend to think they can.

Most of it actually makes a lot of sense.

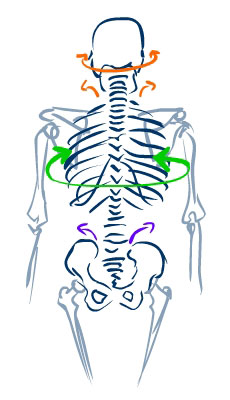

Summary:

The Cervical spine – the neck:

Can move in all directions.

It flexes forward, to the sides, extends backwards, and rotates right and left.

The Thoracic spine – the chest, where the ribs are attached:

Can rotate.

It practically does NOT bend forward or backwards.

No, it doesn’t!

The rib cage contains the lungs and the heart, and helps to keep their volume. If your spine could bend back or forth at the ribs, your lungs would collapse and your heart will get squeezed, and not in a good way.

The Lumbar spine – the hips, the part between the last rib and the pelvis:

Bends in all directions, but does not rotate.

The Pelvic spine, Sacrum and Coccyx (tail bone):

This part of the spine has no movement at all.

This is a group of vertebrae which are fused together to form the back wall of the pelvis.

Basically, this is what you need to know to make spine animations realistic.

There is more to it, though.

The first two vertebrae, Atlas and Axis by name, deserve special attention, and so do other parts of this amazing structure.

WHY, and HOW, do the parts of the spine move they way they do?

First, let’s take a look at the building blocks:

Structure of the spine

Anatomy for artists and for animators in particular, talks about bones and muscles. Here we will look just at the bones, because it is their shape that restricts the movement.

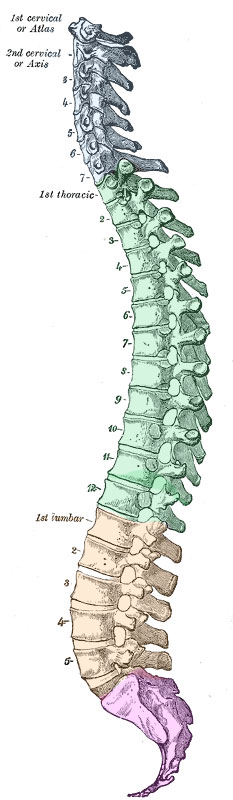

The human spine consists of 33 vertebrae, stacked on top of each other like modular building blocks:

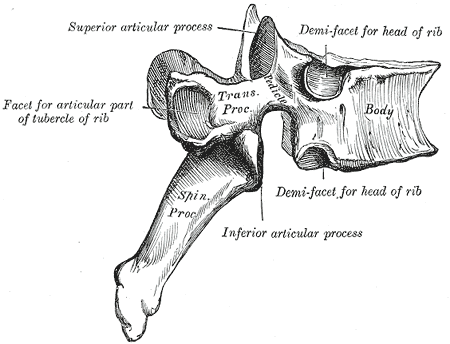

one vertebra, as seen from the side

one vertebra, as seen from the side top view

top view

Essentially, they are all built the same way, but the different parts that make up each vertebra –its body, spikes (processes) nooks and crannies – are modulated according to the location of the vertebra down the spine.

These variations in the shape of the bones restrict or allow movement in different directions.

Look how the shape of the vertebrae changes as we move down the spine.

At the top they are all very thin and “open”.

They don’t need to support a lot of weight, only the head.

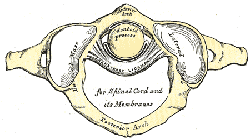

They do, however, need to let the thickest part of the spinal cord pass through, from the brain down to the body.

As we go further and further down, the spinal cord becomes thinner as the nerves fan out to the body and the limbs, and so the Neural arch (the hole through which it passes), gets smaller.

The Body of the vertebra, on the other hand, needs to support more and more weight.

The lower vertebrae become massive and thick in order to hold up your lunch and everything else you carry above the waist.

See the spikes that poke out the back?

These are the bones you feel when you run your hand down your back.

They play a HUGE part in restricting spinal motion.

What are all these spikes for?

Some of them form the joints between one vertebra and the next.

Some are anchors for muscles.

In the Thoracic spine, you’ll see cup-ended processes. They are part of the rib-spine joints.

Between vertebrae are intervertebral discs (or intervertebral fibrocartilage). They too absorb the shocks, distribute the pressure around the joint, and they also help holding the spine together.

The first of these “gel cushions” appears between C2 (Axis) and C3, and the last is between L5 and the Sacrum (S1).

The spinal movement is allowed thanks to these soft-jell-disk joints.

It’s the shape of the bones that restricts the direction of motion.

Check out this link: see the bottom of part 2 in the article (link opens new window)

When discussing the spine, we divide it into 4 sections:

Cervical Spine

This is your neck.

The first 7 vertebrae, counting from the top down, are named sequentially C1, C2, … down to C7.

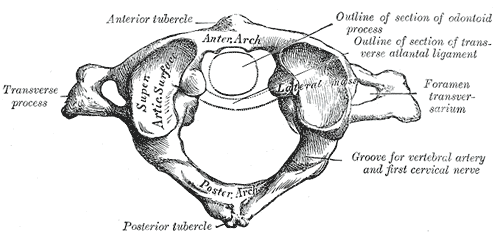

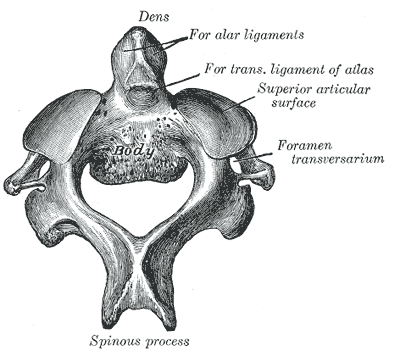

C1 is also named Atlas, after the mythological character that carries the world on his shoulders, because this is the vertebra that the skull sits on.

C2 is named Axis. As its name suggests, it is the axis around which our head rotates right and left.

Both Atlas and Axis are unique in structure and in function.

Their shapes allow the nodding movement and rotation of our head.

I could write a yarn about this, but there’s nothing like seeing these two in action.

Here's a good video that shows it:

I remember learning this in anatomy class and thinking- this is So Cool!

The rest of the vertebrae that form the neck look and behave “normally”.

The spinous processes – the spike poking out the back - are almost flat, and they points just a bit down, allowing the neck to bend backwards quite a lot before they collide and stop the movement.

The natural structure of the Cervical spine curves forward, to the front of the body, and this curve has a name:

The Cervical Lordosis. (Lordosis being the name of “curving forward”.)

The spine has 4 curves, as you will see.

They help absorb the shocks that the spine sustains through walking, jumping, and lifting cars (if you are Superman).

Thoracic Spine

This is the chest, the part of the spine to which the ribs are attached.

It consists of 12 vertebrae, named T1 to T12.

It naturally curves backwards, in the Thoracic Kyphosis, (Kyphosis meaning “curving backwards”).

The ribs are attached to the spine in a rather complicated 3-point joint.

On one hand, they (the ribs) need to be able to rotate up and down.

This is how we breathe – by expanding and contracting the chest.

On the other hand, you don’t want them to move too much, or the lungs will collapse.

Look at the spinous processes at the back of the Thoracic spine, especially T4 –T9. See how they are pressed hard down on top of each other?

This lockdown prevents the spine from bending backwards.

Parts of the vertebra that point up and down prevent rotation, and limit forward flexion.

The primary movement here is Rotation.

Try it in front of a mirror.

Now see if you can tell that the next part of the spine does not rotate at all:

Lumbar Spine

This is the hip area, between the ribs and the pelvis.

5 vertebrae, (getting thicker and massive), named L1 to L5.

They curve forward again, in the Lumbar Lordosis.

"MASSIVE" is the key word here.

It actually makes a lot of mechanical sense not to allow rotation here.

The chief danger would be sheering off the spinal cord (Aghhhhh… !!!)

The Lumbar spine can bend a lot.

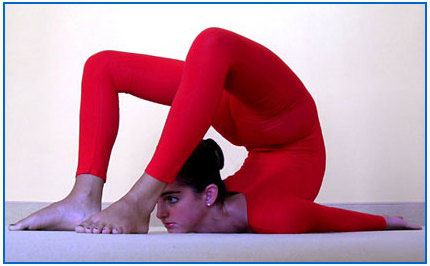

When you see a contortionist bring her legs up and over her head - most of this bending is done in the lumbar region and in the neck.

You need very long muscles and a bit of good (or bad?) genes, to be able to do this sort of thing.

Pelvic Spine

The lowest part of the spine.

All the vertebrae here are fused together to form the back wall of the pelvis.In many sources you’ll find this part of the spine divided in two:

Sacral: 5 vertebrae, S1 – S5, fused together to form the Sacral Kyphosis.

Coccyx: The “tail bone”, made up of 3 to 5 vertebrae, also fused together.

There is no movement here, obviously.

Learn more

If this kind of anatomy is interesting to you, you may wish to learn a bit more.

Wikipedia is a good place to start. True, it's not specifically "anatomy for artists", but you can follow the topics that interest you.

Look up “Vertebral column”, and go on from there.

There are several good books on human anatomy for artists. They show skeleton and muscles, and explain how the joints work.

The next thing to learn is how the shoulder girdle sits on top of the rib cage, and how the muscles operate it.

I know how much my own animations have improved since I learned some anatomy!

Your Own Spine

When researching this article I naturally came across all the “back pain” web sites and couldn’t help noticing my own, computer-induced neck pains.

If you're like me, sitting many hours at your computer, do be kind to yourself!

Get a good chair and a foot rest; put the screen up at a bit below eye level.

Get up and stretch every hour.

Otherwise we'll all end up looking like Goofy :-)

A visit to the Body Worlds exhibition

Figure Drawing Journal:

In This Section

Basics:

More Drawing Tuts:

anatomy- the movement of the spine

drawing perspective with a single vanishing point